Meira Smit is a student at Macalester College who participated in the River Semester trip in fall 2023. These reflections explore her time on the river, in Minnesota at the beginning of the trip, and in Louisiana close to the river's mouth.

Manomin in Northern Minnesota, September

Our time with Manomin reminded me of a lot of harvesting hay on my family’s sheep farm. Harvest time for hay is the hottest part of the summer, you need to wear long sleeves and pants to keep the sticky, sharp, grasses off your skin. Despite this obvious discomfort, the work is deeply rewarding and brings me satisfaction when I see a barn full of hay that will feed the sheep all winter, or when we spread several canoes worth of rice on a tarp. During our week at the Water Protector Welcome Center in Palisade Minnesota, we harvested, parched, jigged and winnowed Manomin or wild rice with Dakota and Ojibwe teachers and elders and members of Honor the Earth. Our group worked together for the first time, and we bonded over meals with the grain we had directly labored for, not purchased.

9/2 Saturday

Wild ricing morning

Early in the morning we loaded seven canoes, paddles, PFDs (personal floatation devices), knockers, and push poles and drove to the lake.

Resembling a grassy meadow, the wild rice grew tall and opened up in pathways for canoes to move through.

I sat in the bed of the canoe with two cedar knockers while Timea stood in the back with a 12-foot pole.

Pushing the pole against the lake bed, we glided through the meadow of manomin, cradled with stability of the vegetal mass. We had little risk of tipping.

A few hours went by gliding through the rice and the “pit” “pat” “whoosh” of rice grains falling in the canoe. Everyone returned with the bottom of their canoes full of rice and bugs. We bagged it and returned to the Water Protector Welcome Center.

I sewed the rest of the day; canvas moccasins for gigging and bags for the gigging holes.

My new crew mates and generous hosts impressively embodied love, patience, and hard work.

Manomin in Southern Minnesota, mid-September

It is mid September, before the equinox. The days are long. Near my origin, at the confluence of the Chippewa River and the Mississippi River. Feels like home. In a back channel of the river where the dam created shallow wetlands, the boat drifts through four feet of nearly still water. Unlike the main channel with sandy banks lined with cotton wood and silver maple, with their feet tangled in a thick understory of vegetation, this channel the water meets green thickets of tall grass. Manomin, or wild rice, is actually a cereal grass, like wheat. I recognize the right conditions for Manomin; shallow, slow moving water, like we encountered in the lakes of northern Minnesota. The tall grain reaches for the sky with equal mightiness as it anchors in the soft organic muck of the river bed. Manomin is steadfast despite rising and falling water levels, motor boat current, nibbling waterfowl and water mammals such as Mallard ducks and muskrats. Stifling competition, partnering lily pads shade other aquatic plants like cattails. Manomin invites you to be cradled, in its sturdy stalks and abundant nutrients. In Palisade, Minnesota, Manomin gave us gifts of memory, friendship, hospitality, and food. In an attempt to reciprocate and at the request of Betsy, Anishinaabe elder, we toss balls of clay laden with its seeds to germinate in the coming spring.

Sugarcane in Louisiana, November

November 2023: North of Baton Rouge, on a stretch of the river rightfully called Cancer Alley—but more commonly branded the “Chemical Corridor” by those that profit from it—smoke clouds, produced from the remnants of harvested sugarcane, plume behind the levee and dissipate along its banks. Despite widely used harvesting methods that are more environmentally and lung friendly such as using the leaves of the cane for compost or mulch, fire is still used here to burn off the dried leaves and other non-sugar parts of the sugarcane stalk; burning keeps overhead lower for the sugar industry. We can smell the small particulate matter and other toxic compounds, such as ozone, carbon monoxide, and nitric oxide. This somewhat pleasant, sweet aroma has entered our lungs with a discomforting familiarity on our trip down the Mississippi. Further down the horizon is a cumulus cloud, lonely in the sky among a smattering of high elevation cirrocumulus ripples as depicted in my painting, Cumulus Cloud near Whitney Plantation. The cloud stands out from the landscape like a feature in an obnoxious popup card against a 2D-landscape. This phenomenon is evidence of a strange but commonplace human meteorological impact, a byproduct of oil refining in which volatile hydrocarbons coalesce with moisture.

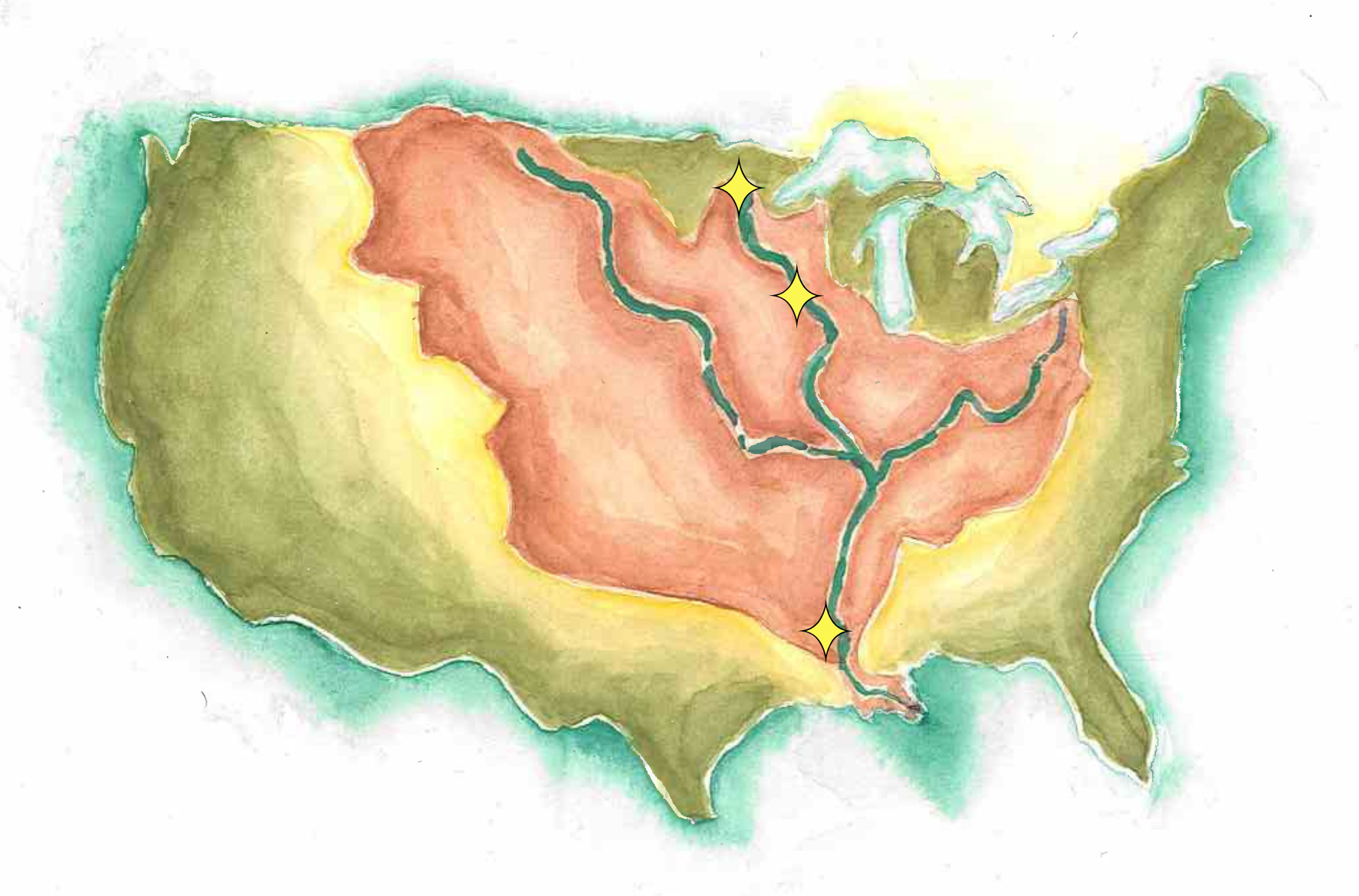

Evidence of human impacts are particularly apparent in Southern Louisiana. In a conversation with a geomorphologist, who studies coastal land loss there, I was introduced to the term “palimpsest” in the context of geological formations and sites of extraction along the Mississippi River. Palimpsest refers to something that is changed or changes but resembles and retains traces of its earlier form, and often the layers influence the following layers. This is easy to see in river deltas like the Nile River delta in Egypt, where the soil is rich from layers of silt deposition. Economic wealth is built from the land’s ability to produce and conflict arises over who gets to control those resources. The river delta is like the earth itself. It is made up of layers of sediment going back millions of years whose individual layers can still be read by its traces. The geomorphologist described how land is formed in certain regions in a way that mimics that of the previous era, influenced by environmental conditions but also by historical events. I am building my own psychogeography, an emotional, mental, and geospatial understanding of this section of the river. Using the concept of a palimpsest helps visualize the patterns of history as they are enacted through extraction, oppression, and production on this land.

Today, Cancer Alley, once attractive to colonizers for its rich river delta soil and proximity to freshwater and ocean ports, endures significant burdens on its land, water, and inhabitants. Arriving on our boats for a site visit to the Whitney Plantation in Edgard, Louisiana, our walk over the levee, and our stay on the adjacent river’s edge presented evidence of the deposition of trauma and continual laceration. At the plantation museum which memorializes experiences of enslaved people, our tour guide –the historian Ibrahima Seck –-brought us through preserved shacks of the enslaved at the edge of an old sugarcane plantation. In catalogs, we read the names of hundreds of children who died from the horrid working and living conditions. In silence, our group soaked in the memorial to the revolutionaries lost in the “German Coast” uprising of enslaved people of 1811.

Leaving the plantation grounds, these ruptures in North American history shined upon all following encounters. Our group walks through a sugarcane field, today being harvested by an air-conditioned tractor, over a levee that was built using enslaved labor. As we climb through the batture (the land between river and levee), we encounter inmates working on the tow boat through a work release scheme—functionally imprisoned on the tow boat. The density of oppression is put succinctly in the article “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America.”Historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad quotes Whitney’s executive director, Ashley Rogers, “You passed a dump and a prison on your way to a plantation… these are not coincidences” (Muhammad, 74). The shadow of the plantation economy’s continued violence looms over the land as the hydrocarbon cumulus radiantly dominates the evening sky.

Though now distant from this land, it remains familiar to me through the stories of family members who toiled in the South and migrated north three generations ago, where their hard work continued. Imagining the labor in the extreme heat and swimmingly dense humidity evokes a sense of grief, as the scene resembles a distant memory. As a visitor now, immersed in this history and yet still breathing in the so-called successes of globalization and colonial capitalism, I desire to resist numbness and demobilization. I question daily how my upbringing in the North allows ignorance and even complacency of this history and present, simply because we don’t have to see it every day. Living in the progressive state of Minnesota protects me from many environmental hazards, yet in many ways I benefit from the suffering of people breathing and drinking pollution elsewhere. I benefit from the ways fellow Black people shaped and suffered for this country. And I benefit from those who still remain there doing the labor we choose not to acknowledge, or who are simply being exposed to the externalities of chemical production. As part of a population of beneficiaries, I wonder if the suffering will catch up to us.

The commodification and subjugation of sugarcane and the land that we see today echoes the same atrocities inflicted on other humans in the past and present. Throughout the model of “conventional” agriculture, which evolved from the plantation system reliant on enslaved labor, the methods involved (not the farmers necessarily) have attempted to sterilize, standardize, and control the soil and supporting ecosystem. This approach has led to increasing use of excessive tillage to make planting easier, artificial agents for bigger and better yields, and militarized defenses against invaders, such as nitrogen fertilizers and herbicides and pesticides. In a vicious cycle that is both expensive and damaging to the health of humans and ecosystems alike, this practice facilitates the further abuse and creation of degraded soil. This happens by violently pummeling the existing life in the soil—nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers then replace the nutrients created by organic matter and the herbicides and pesticides ensure that nothing but the crop can survive. In the end, very little organic material remains, the most essential thing for plants to grow in a healthy ecosystem. Organic material, referring to the complex ecosystem made up of decomposing bacteria, bugs, and fungi, can more effectively and efficiently make minerals and nutrients biologically available, and enable plants to have natural defenses. How long can these conventional practices persist, one might ask, until the soil, no matter how many chemical injections it receives, cannot produce the crops our society depends on?

Considering the impact of these practices, I often think about plants and intra-species interactions and how our relationships with them shape our culture or vice versa. Can our communion with these creatures repair these distraught relationships we have to our human relatives who share this river with us, reflecting that environmental justice is social justice? Perhaps it lies around the dinner table and among our dessert forks and our exhaust pipes if humans are relegated to our role as consumers of commodities. By paying attention and participating with the natural world, humans can recognize that we are not the only species sharing this planet. What kinds of relationships existed in the past and could exist in the present and future?

Take, for instance, sugarcane. This plant, which becomes a word that hangs heavy and saccharine on the tongue, has a history steeped in exploitation—sown in stolen land with stolen labor to please the taste buds of Europe. The cultivation of sugarcane has led to significant environmental degradation, polluting the air with its smoke and making it difficult for us to breathe. By acknowledging this history and understanding the broader impact of sugarcane cultivation, we can begin to see the interconnectedness of environmental and social justice. Paying attention to the way sugarcane has been produced and the suffering it has caused can lead to a greater awareness of our role in the ecosystem and help foster human humility.

Amendment in July 2024, back in the North: It is easy to forget these scenes. Sensitivity diminishes with time and distance. Looking, smelling, feeling back; those sensations are canned and sealed for me as I read this account. I don’t want to forget, but I also don’t want to actually feel it again, because it hurts and I’d rather not rot in grief. Remembering the smoke and heat and drinking water during a drought while the cracked sand begs you to share a sip of whatever you’re drinking, while rain refills perpetual puddles on my sidewalk, and exceeds river banks to levels unsafe for small vessels. The North is really just beginning to experience these so-called effects of climate change; it is harder and harder to deny when a snowy state doesn’t receive snow in a winter. We have much to learn from our neighbors in the South about how to adapt (or not) for what is to come.

An earlier version of the sugarcane essay was published in the spring 2024 issue of Imani, Macalester's Black student publication.