From May 25th to May 28th, 2023, the distributed collaborators working on the Mississippi River Open School for Kinship and Social Exchange gathered in the Twin Cities for Confluence 2, an annual gathering of river hubs to share past activities and plan for the coming year. As Confluence 1 was online, this was the first in-person gathering of the entire Open School group. For some, it was a chance to reconnect with longtime collaborators and old friends, for others it was an opportunity to get to know people who they had only met over email or video meetings. The Confluence was packed, with visits to a variety of sites, conversations with activists, historians, artists, and scholars, and time for connection and collaboration. Highlights include a trip to the Headwaters Hub in Palisade, Minnesota, a bus tour through environmental justice-related sites in North Minneapolis, and a sunset riverboat cruise down the Mississippi with Indigenous storytellers. Attendees from the Lower Mississippi Hub included four graduate students from Southern Illinois University Carbondale, who were relatively new to the grant project. We present here four reflections, one from each of the four grad students, that we hope will add up to a multi-faceted portrait of Confluence events and their impacts on attendees.

On Living — Ebru Bodur

As a former activist, a Ph.D. student, and Sarah Lewison’s assistant, I had the chance to travel to Minneapolis for the 2023 confluence. It was a unique experience focused on environmental activism and building a healthy community in the activist world. Before thinking about my experience in Minnesota, it might be helpful for the reader to know more about my activist past in order to understand this trip’s effect on me as a person who quit activism (at least, no more “field work”) a couple of years ago.

I have decided to intercut these personal reflections with one of my favorite poems by Nazim Hikmet Ran called “Yaşamaya Dair” (On Living) which illuminates my relationship with activism. He was one of the most famous poets in Turkey but spent more than a decade in captivity. He was a communist and part of the TKP (Turkish Communist Party). His poems were a key part of his activist work, even this poem, written in 1948 during his imprisonment. In one of his darkest moments, he reminded himself and later us that we need to live and never give up. There is no way to compare his suffering to my relationship with activism, but Ran’s poem enlightened my path to healing this damaged relationship.

Yaşamak şakaya gelmez,

büyük bir ciddiyetle yaşayacaksın

bir sincap gibi mesela,

yani, yaşamanın dışında ve ötesinde hiçbir şey beklemeden,

yani bütün işin gücün yaşamak olacak.

Living is no joke,

you must live with great seriousness

like a squirrel for example,

I mean expecting nothing except and beyond living,

I mean living must be your whole occupation.

I met activism when I was an undergraduate student in Turkey. I had no family or friends involved with activist work. I’ve never had a guide or mentor teaching me how to build a community in an activist world. I now know the difference between an organizer and an activist. Still, at that time, my dreams were big enough to bravely attend meetings at the university and outside school activities. I started my journey by following the political party’s youth group meetings. I was motivated by the long tenure of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan who had been president/prime minister for a decade and has now been in power for 20 years. When you’re an 18-year-old history student in a vibrant environment, you almost feel invincible. At the same time, I was particularly interested in revolutionary history (which later became part of my thesis during my undergraduate degree). Reading about different revolutionist groups fighting against the government/empire/feudalism/capitalism… whatever they found unjust and oppressive, was inspiring and motivating. The thought of criticizing AND changing the country with our actions filled me with hope and energy.

On the other hand, just like most young people in Turkey, I was also angry. The first time, I felt that anger when one of our professors told us the government sued her because of her anti-government political activities and that she could go to jail. I was utterly shocked. With uncertainty, we waited for the court day. Eventually, the judge gave her a 5-year detention, and she would be under surveillance for five years. This means that the government would follow her every action, and she would go to jail if she did something they found inconvenient. This unjust incident made me think about my own actions. I picked academia as a professional space because it would provide me with the freedom to discuss ideological elements among intellectuals and younger people. I was aware of academia's institutional and administrative sides, but it also contained less hierarchy and limitations (at least, that’s what I thought). However, my professor’s incident reminded me of the academic atmosphere in Turkey. It did not contain freedom; instead, it was surrounded by structural fences that controlled the country's educational space, directly affecting the type of education the universities held.

Diyelim ki, dövüşülmeye değer bir şeyler için,

diyelim ki, cephedeyiz.

Daha orda ilk hücumda, daha o gün

yüzükoyun kapaklanıp ölmek de mümkün.

Tuhaf bir hınçla bileceğiz bunu,

fakat yine de çıldırasıya merak edeceğiz

belki yıllarca sürecek olan savaşın sonunu.

Suppose for something worth fighting for,

suppose we are on the battlefield.

Over there, in the first attack, on the first day

we may fall on the ground on our face.

We will know this with a somewhat strange grudge,

but we will still wonder like crazy

the result of the war that will possibly last for years.

After my professor went to prison, I decided to do anything I could to change this cycle of fear, the process of surveillance, and the power that comes with it. I attended protests for the new airport because the location was on the birds’ immigration path. I protested for no canal project in Istanbul because it would pollute the water and the canal would carry extreme risk for possible earthquakes. I opposed the new presidential system, which gave immense power to the president, and the parliament would not have any say in the decision-making process. I protested construction amnesty so people would build more sturdy buildings since the country is in the fault zones and open to extreme earthquakes. I protested the journalists and academics in prisons or forced to retire while the real criminals live free. I stood with queer communities who are genuinely marginalized, have no rights, and constantly face violence.

My last major activist event was about Mount Ida—a place of natural beauty in northwestern Turkey. A private company, The Cengiz Holding (a longtime ally of Erdoğan’s) wanted access to a copper mine site under the mountain. The government also licensed 79% of the area as mining zones. People fought against the government’s cruel decision. Many protestors from different NGOs went to Mount Ida and camped there to protect the land and show support to local villagers. Unfortunately, it didn’t work. Most of the forest area in Mount Ida region is gone. I was angry and extremely disappointed because of the failure we experienced. This was the last event that I was part of. The results of Mount Ida and at the same time having some health issues, I decided to leave the country and activism. I was already nervous because some of my friends lost their passports despite receiving a scholarship to prestigious European programs. Because of their involvement with activism, they lost their chance to improve themselves and travel. Therefore, I left the country to attend graduate school in 2019.

Yaşamayı ciddiye alacaksın,

yani o derecede, öylesine ki,

mesela, kolların bağlı arkadan, sırtın duvarda,

yahut kocaman gözlüklerin,

beyaz gömleğinle bir laboratuvarda

insanlar için ölebileceksin,

hem de yüzünü bile görmediğin insanlar için,

hem de hiç kimse seni buna zorlamamışken,

hem de en güzel en gerçek şeyin

yaşamak olduğunu bildiğin halde.

You must take living seriously,

I mean to such an extent that,

for example your arms are tied from your back, your back is on the wall,

or in a laboratory with your white shirt, with your vast eyeglasses,

you must be able to die for people,

even for people you have never seen,

although nobody forced you to do this,

although you know that

living is the most fundamental, most beautiful thing.

I have often thought about the past during my time in the United States. Despite being a woman and queer, I am a privileged citizen in Turkey. I am Turkish and was raised in Sunni Muslim traditions. I grew up in the suburbs of Istanbul and attended private school since kindergarten. My family was upper-middle class (when the middle class existed), and my dad had his own company. Therefore, I have never experienced any hardship living in Turkey. Then I moved to the United States of America, where I’m a queer, Muslim, Middle Eastern/Asian, leftist woman—the complete package to receive conservative hatred. My identity and its meaning altered when I moved here from a privileged citizen to an international student where you have very limited financial and mental freedom (cannot work outside the university, expensive health insurance and school fees, not able to see your family…). At the same time, I was thinking about alternative realities. What could I have done differently to have better results? If I hadn’t “quit” activist work, would I be able to change things overseas? Did people feel betrayed when I left? I had so many questions but not adequate answers…

Bu dünya soğuyacak günün birinde,

hatta bir buz yığını

yahut ölü bir bulut gibi de değil,

boş bir ceviz gibi yuvarlanacak

zifiri karanlıkta uçsuz bucaksız.

This earth will cool down one day,

not even like a pile of ice

or like a dead cloud,

it will roll like an empty walnut

in the pure endless darkness.

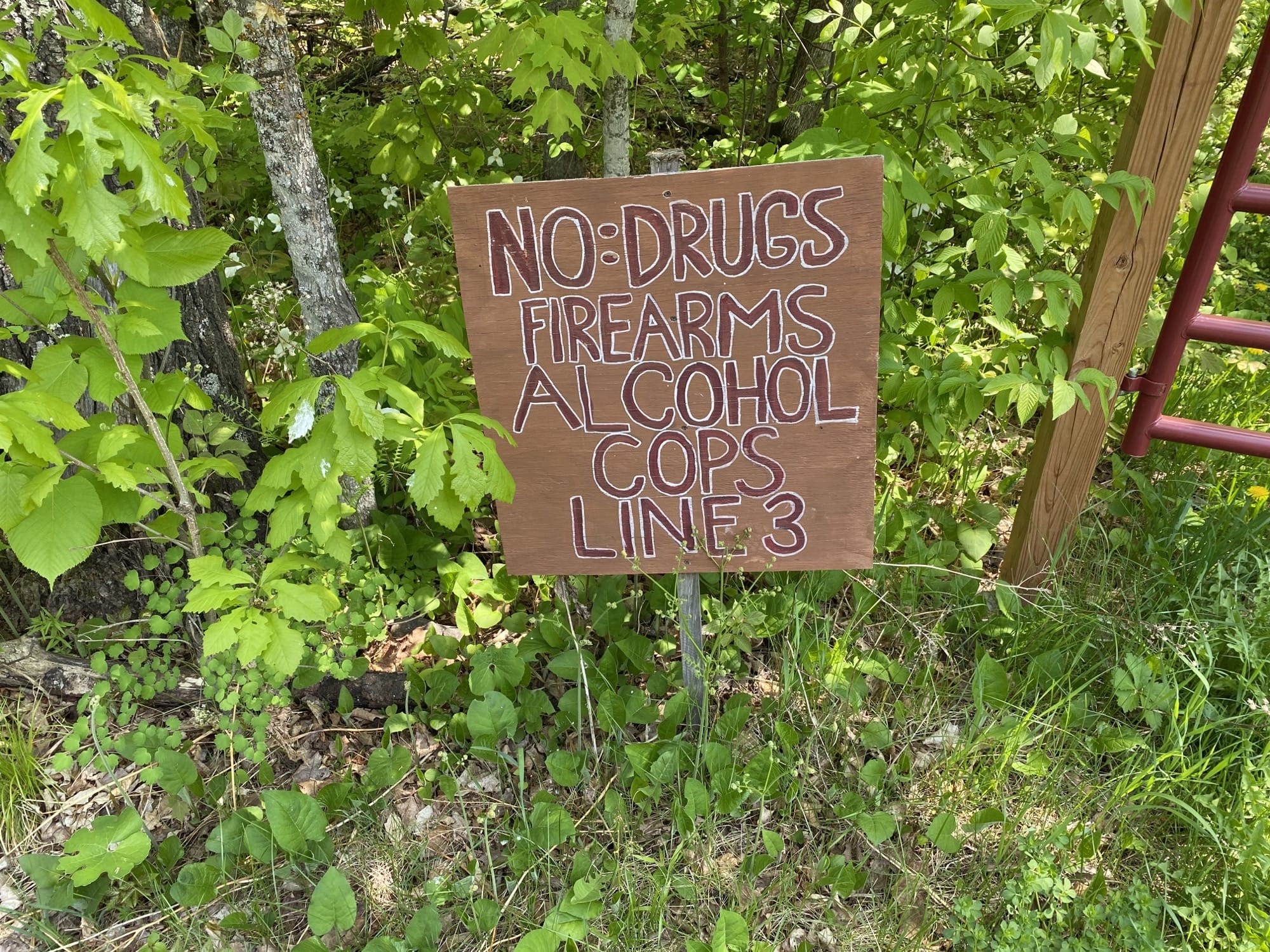

…Until our trip to Minneapolis. First, I was eager to learn about the Line 3 pipeline and its danger to clean water. We have a similar problem with the Canal project in Istanbul. Therefore, I was curious about the activist approach. Now, I live in this country and have family here, which means I feel this urge to dive into the activist atmosphere in the United States. Thus, this would be an excellent opportunity to experience Western activism firsthand. How do people deal with the police? What kind of sources are available to spread awareness? What type of alternative activities that activists use to educate people on this issue? More broadly, how do they attract young people to join them? More importantly, how can we change things? On the first day of our trip, we had a chance to visit the Water Protector Welcome Center, which was used as the base for the pipeline protests during the Stop Line 3 movement. The whole experience simply blew me away.

First, they introduced us to one of the Native elders who lives on the property. Initially, she gave us information about the current issues of the pipeline. Later, she talked about her experience as an Indigenous woman in the activist field. Her mentorship to younger generations was inspiring and an essential element I have never had as an activist. I immediately noticed the intergenerational gap I experienced during my younger years. Failure was an expected result in activism. We are not fighting to get results at that exact moment. I am now well aware that I’m fighting for things that I may not be alive to see. However, the essential part is the process of activism - building communities, informing and educating people about important issues, failing, and being able to start again. This valuable knowledge can be passed over to the elders and mentors who have been there before. They must pass this wisdom from generation to generation or else younger activists will have no guidance during failure and disappointment. I realized that lack of mentorship made my generation cynical and easier to give up in any inconvenience. I could physically feel the power this woman’s mentorship provided for the younger people.

Yani, öylesine ciddiye alacaksın ki yaşamayı,

yetmişinde bile, mesela, zeytin dikeceksin,

hem de öyle çocuklara falan kalır diye değil,

ölmekten korktuğun halde ölüme inanmadığın için,

yaşamak yani ağır bastığından.

I mean, you must take living so seriously that,

even when you are seventy, you must plant olive trees,

not because you think they will be left to your children,

because you don't believe in death, although you are afraid of it

because, I mean, life weighs heavier.

Their dedication felt familiar, but the atmosphere did not, especially because making art was central to their protest. When I was an activist, I never made art. The anger and, later, the disappointment were so heavy that I'd never thought about it. I couldn't even consume content, let alone produce any. I left my country and got into graduate school, which allowed me to explore my artistic approach as a scholar. Creating and criticizing your work as a scholar was such a magical moment. I was incredibly proud of what I was doing and what kind of a scholar/artist I had become. Let me explain this better.

When I arrived at the center and saw how they combined approaches of art and activism, I was stunned. Not only mixing two elements that I had never thought of, but creating art AND protesting by making art was not something I had considered. I am well aware that many artists in the past criticized the system and pointed out the significant lack in our society. When you read about them, you think, "Yeah, that sounds good." But we see them in action today, and the protesters' infusion of artistic elements into their activist work the field was remarkable. At that moment, I realized the opportunities I missed during my early activism. What if we created art during these moments? We could have done so much.

Then, later in the Minneapolis trip, my group and I had a chance to visit George Floyd Square. For me, it wasn’t just a city square. Locals carefully protected the archive of what had happened in that square. It wasn’t square; instead, it was a museum. You could talk to people and get their memories of three years ago. While walking around “the museum,” I could ask people questions and get their thoughts. Additionally, the streets were filled with art about the importance of the place. What a scene to witness!

It reminded me of my first experience with activism. The Gezi Park protests in Taksim Square, Istanbul, in 2013. It’s been ten years since the last demonstrations fighting against city planning. If one goes to Taksim Square, nothing about the protests and people’s collective movement exists like it never happened. While they destroyed all the relics of the Gezi protests, they also destroyed history. On the other hand, George Floyd Square was beautiful and, more importantly, alive. As Nazim said, I felt the grief and pain but lived the moment the community tried to keep those memories alive.

At the end of the trip, I was overwhelmed by the ways in which activism and artwork together. The interaction and unifying facts of art created a unique space. Maintaining and preserving history is a particular task, and Minnesota achieved that. As a given-up activist, this trip began the process of healing me.

Since the trip, I often found myself reading this poem by Ran. Nazim Hikmet Ran was an extremely famous poet, and his style of writing influenced the next generations, although this specific poem of his affected me the most. One of the most essential thematic elements in his poems is loneliness. His expectations from life and society force him to feel alone because there are certain ways of living that Ran thinks we should do more to change the social environment. That’s why his poem tells us about how much he loves living and at the same time how much he feels lonesome in this idea of living. Nevertheless, with his repetitive lines, the emphasis on life is highly cherished in the poem. No matter what, he did not give up and his words inspired me that if Ran could still be hopeful in prison after people called him a traitor and worse while he wanted to change people’s lives, I could manage to revive my passion for activism and art.

From now on, I will take my steps slowly but surely.

Anticolonial Process and Performance – Nick Karpinski

Much of my work as an MFA film student at Southern Illinois University revolves around process. I’m interested in flux and spontaneity in my artistic practice, which has resulted in a metanarrative film that I’m currently (and ongoingly and recursively) working on for my thesis. However, in introducing this essay, I feel as though I shouldn’t be talking about myself, but I should be talking about the amazing people and things that I encountered as a part of the Open School’s trip to Minnesota—listening to Indigenous activists and storytellers, listening to water protectors and scholars, and encountering and being with the Mississippi River. I do believe, though, that ideas revolving around process, experience, and self-referentiality have very much to do with the Minnesota trip, and the process that existed/exists there, which might be telling of the infinitive words that I used to briefly describe what occurred during the trip.

To backtrack just a bit, I was introduced to the Open School in 2022 through a summer class titled “Decolonizing Spatial Sovereignty.” In the class, we discussed colonialism’s persistent effects upon place. Additionally, we traveled throughout Carbondale, Illinois and then to Cairo, Illinois and Memphis, Tennessee. In doing so, we thought about place and our various positionalities in relation to colonialism.

After taking that class, and now, traveling to Minnesota for similar discussions and travel methods, there certainly is a link between Decolonizing Spatial Sovereignty and the Open School Minnesota trip, especially regarding the process of anticolonialism, which is inherently tied to the materiality of place. In other words, there should always be a grappling with the specificities of place, because places—in this case, Minnesota—are affected by colonialist milieu. Ecological environments, such as waterways (the Mississippi) have been stripped of their resources through excessive mining. Neighborhoods have inherent inequality due to institutionalized racism. Practices such as these exist because of leftover colonialist ideology that was brough to North America through genocide in the 15th century, and we should be constantly grappling with and drawing attention to that fact.

Perhaps a good example of this grappling is when we traveled to the Welcome Water Protector Center in Northern Minnesota:

As a group, we walked down to the river. The sun brightly beamed down from the completely blue sky, unincumbered by a single cloud. The sky’s hue was like a chlorine pool on a pristine summer day. As we got closer to the river, making our way through brightly alive shrubbery, the mosquitoes awoke and made their presence known. They glided toward us, like a stampeding herd of buffalo, animals that once thrived in the Minnesota prairies. The mosquitoes smelled our fear and latched onto us as we combatted them with bug spray—bringing minimal relief from their mission to draw our blood. Bzzzzzzz. Bzzzzzzz. Bzzzzzzz. Bzzzzzzz. They screamed out a fight song as their wings fluttered.

Nonetheless, trudging our way past them, we made it to the river, walking across its thick, brown, muddy bank, which sat atop the extractive Line 3 pipeline, a pipeline that the water protectors, the people who we came to visit, have been protesting and mourning for years. We stood on the bank. We stood witness to the Mississippi. We stood on Indigenous land that has and continues to be raped by colonialism.

This type of description is similar to what xwélmexw artist Dylan Robinson calls performative writing—writing that uses an embellished “sparseness, or roughness to convey something about the subject in question: it attempts to elucidate the non-representational aspect of the subject through forms of sensuous, material textuality” (85). Performative writing hyper-fixates on people, objects, and things. It allows the writer and the audience to unpack their relationship to environments within the context that Christina Sharpe would call “the wake.” In her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, she says the wake is the current place where Black life exists in the contemporary postcolonial context. Sharpe uses the “wake” of a slave ship as a metaphor for that context—as representative of the aftermath of slavery. She also pairs the wake with our need as a society to work to heal colonial wounds that have damaged both people and land:

we might continue to imagine new ways to live in the wake of slavery, in slavery’s afterlives, to survive (and more) the afterlife of property. In short, I mean wake work to be a mode of inhabiting and rupturing this episteme with our known lived and unimaginable lives. (18)

Living in the wake requires a process of work with all people, and the environment, to create healing and resistance against superficial colonial knowledge that presents itself as certain and correct. For instance, the water protectors that we visited, through protest, resist the colonialist idea that the Line 3 pipeline must exist to yield profit without a reciprocal relationship between land and people. This colonialist profit-making agenda is a grain of salt that lies in the midst of thousands of years of Indigenous knowledge—knowledge that nurtured our environment, and certainly didn’t prompt our ecological crisis, a crisis which is situated in the wake of colonialism.

It’s the job of all those who live in postcolonial society to contribute to the process of unsettling colonial thought and practice. Within that process, the white members of postcolonial society must support the nonwhite voices that have been silenced and disregarded by colonialism. This will hopefully create a web of collaboration and spark a togetherness that is antithetical to colonial division. It will take work, it will take discomfort, and it will never be complete. We will always be working, and we will always be imagining healthier futures. And that combination is necessary, because it is what we have at our disposal in the current state of the world. It’s what we were doing in Minnesota. It’s what we were grappling with.

All these ideas are large aspects of what I took away from the trip and are ideas that I will apply to my own work. In conclusion, I want to state that we need to emphasize the metamorphosis between work and imagination: materiality and immateriality. We need to imagine anticolonial futures and tangibly work to proceed in an anticolonial direction. Before I left Minnesota, I stopped at a local bookstore. In the poetry section, I saw a book titled Wail Song: wading in the water at the end of the world, by Minneapolis poet Chaun Webster. The piece is a longform experimental poem in conversation with Sharpe’s In the Wake. Relating to the imagination, Webster says, “Make a maroon, a saltwater wraith. Make an underwater country Drexciya deep in the black atlantic. Make our body part of the storm, unsettle the water” (91). Drexciya was a 1990’s/early 2000’s Detroit techno Afrofuturist group. Afrofuturist art uses the past to think forward and imagine new futures. It simultaneously grapples with colonialism and escapes it—and that’s what all art should do in the wake of colonialism. Like performative writing, in postcolonial society, we must constantly grapple with our respective positionalities to colonialism. That grappling should exist in all art because art reflects society—society in the wake. Artwork is wake work, just as activism is, just as teaching is, just as science and technology is. Wake work is holistic and requires all driplines. So, I hope that this essay, and I hope that artmaking, is in conversation with a wide range of works regarding a wide range of disciplines. For art specifically, though—since, as an MFA student, I’m writing from an artistic perspective—imagination is central. As Webster says, we can make, and we can imagine, and we can do. We can work to form a new society. In order to form a new society, we must first imagine, and art’s job is to sincerely imagine. Then, colonial ideology might evaporate and bring about material change through a collaboration of anti-colonial work. Through that process, I look forward to imagining and supporting others while wading in the water at the end of the world.

Nothing Goes Away – Kendra Keefer

For me, activism has often been lonely and isolating. Confluence 2 was transformative in that it reminded me, deeply, that I am not alone. I gained more than I can list, but highlights included: new strategies for working with groups, experiences like the visit to the Native Canoe Program at the University of Minnesota that I will never forget, an herbal first aid kit, and, most importantly, a treasure trove of ideas and conversations to carry home with me and ponder.

One such conversation took place on the first day of the conference. While walking away from the Talon Mining facility with a group of attendees, Joe Underhill stated, that whenever he is evaluating the merit of an industrial extraction project, he keeps the idea that “Nothing goes away” at the forefront of his mind.

Having just come from visiting my mother, where she lives on 18 acres at the opposite end of the Mississippi with limited trash pick-up, the idea of ‘nothing every going away’ resonated with me. I was reminded of how odds and ends—old toys, glass milk bottles, pieces of china—from generations past would wash up from the mud, out of time, after a big storm.

In my mind’s eye, I also contemplated the fence in front my mother’s house, welded together from scrap metal, including augers that were likely byproducts of the oil and gas industry. Like a river, a fence is both a connection and a boundary. It connects what it stands between while cutting what was once a larger whole into separate smaller pieces. For domestic animals, fences provide safety—the scrap metal fence protects my horses by separating them from the road. It is also one of the more benign examples that nothing goes away.

The Welcome Water Protectors Center—Welcoming

I arrive in Minneapolis frayed and distracted from juggling graduate school with driving long distances for work and family obligations. When we get to the hotel, I drop like a stone into my bed. The next morning, I am tired but eager to see the Welcome Water Protectors Center.

On the bus, I use my time to draw and study leggy pine trees through the window, to read the books I brought with me (David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass), and to get to know my seatmate, who is around the same age as my son.

She and I compare notes about living on a small-scale farm as a child (her experience) and as a parent (mine). Our discussion is the first of many and it provides me with a pathway out of my head and into the group.

Over the next three hours the road narrows and winds through a vast forest that is impossibly green against an impossibly blue sky. When we finally reach our destination, the bus slows, makes a U-turn, and jerkily nestles itself into one of the shaggy emerald walls lining the naked highway. We disembark next to a rainbow sign on a narrow gate requesting us not to block the driveway.

The wooded pathway on the other side of the gate is a patchwork of deep shadows dappled with hazy rays of sunlight, raucous with birdsong and insects buzzing. We follow the path until we are deposited into a sunny clearing with a contemporary-looking house sitting cozily in the middle. The left side of the house is wrapped in a large deck. To the right, I can see brightly painted signs from the 2021 Stop Line 3 Protest and a wooden structure that reminds me of a horse mounting platform to the right of the house. Looking into the woods, I see a yurt decorated with geometric patterns. Bright blue bundled-up tarps, and a handful of tree stump stools gather in a circle in the woods as if for a meeting that has caused them to slump over in exhaustion. In front of everything is what I immediately take to be the heart of the Welcome Water Protectors Center: a gently smoking fire pit, ringed with chairs of varying shapes and sizes.

In 2021, The Welcome Water Protectors Center was the site of a standoff between water activists and multinational energy corporation, Enbridge, Inc. That winter, three hundred people traveled to a remote, heavily forested location in Northern Minnesota to camp in snow and ice, to protest the continued expansion of the Line 3 Pipeline. Line 3 is an oil pipeline that crosses the Mississippi River several times. The land activists camped on was purchased by Honor the Earth, a native-led environmental advocacy nonprofit, as a legal strategy to try to stop the pipeline’s expansion. Activists were concerned that an oil spill at the headwaters of the Mississippi River could contaminate the entire Mississippi River Basin—the fourth-largest water catchment system in the world.

It is lunchtime and we fill the chairs around the fire pit until they are overflowing, with attendees sitting on the ground and the edge of the deck. As we drink delicious herbal tea and eat locally made sandwiches, the Water Protectors share testimony about the Pipeline 3 protest in 2021. One activist, Tanya, explains that her participation in the protest was prompted by her beliefs as an Anishinaabe woman who feels a special responsibility to steward the headwaters of the Mississippi River, her ancestral home. She hopes to protect the water, not just for her own children and grandchildren, but for all the living beings who live along the river and its tributaries.

I think of my mother and extended family, living in the Red River Valley of the Caddo Nation homeland. Many of my relatives are purposely ignorant about climate change and I doubt any of them were aware of the Line 3 protest. I am touched that Tanya’s caring can travel so far.

Nothing goes away.

Two hundred activists were arrested, including Tanya. She shares how dispiriting it was to explain her police record and her parole officer to her family, but still remains hopeful. While she and the other activists didn’t stop Line 3, they brought nationwide attention to the problem and created a network of people who remain engaged on issues surrounding the natural environment.

Nothing goes away.

After lunch, we walk down the bare highway to see the Mississippi River and the site of Line 3. As we walk, John Kim and Haze, another Water Protector, share stories from the protest. As I listen to them, I try to imagine the noisy music of summer birds and insects replaced by the quiet of snow and the sounds of three hundred people living and working together.

When get to the river, it is hard to believe that this large creek is destined to become the giant Mississippi River I spent my childhood crossing on road trips back and forth between Illinois and Texas. Here, in its marshy, muddy infancy, the river is barely bigger than the creeks on my mother’s farm and reminds me of streams I have kayaked in Southern Illinois.

As we walk back to the house, I notice cloth prayer flags protesters left in the trees. The pieces of white fabric, with their thought-over, prayed-over, cared-for words transformed into grey splotches from the rain and snow, flutter softly like memories, in the trees.

Nothing goes away.

Talon Mining Facility — Crossing

Eventually, we board the bus again to travel through land where wild rice (manoomin) grows. Speaking into a loudspeaker so everyone on the crowded bus can hear, Tanya explains how manoomin is harvested and prepared, and the role it has played in sustaining the Anishinaabeg, even during hard years when the United States government withheld food and supplies from the tribe as a strategy to starve them off of their land. The Anishinaabeg believe that manoomin is a sacred gift given to them for sustenance and survival. Tanya and many others are concerned that nickel mining, which is being explored in the region, will pollute the waterways where manoomin grows.

Our next stop is in a small town that could be anywhere in the U.S. to observe the Talon Mining facility Tanya mentioned. The facility, surprisingly small and nondescript, is located next to a park. We file off the bus. Some conference attendees go to the picnic tables under the park’s covered pavilion, while others walk over to the mining facility.

After taking a few pictures of the park and its playground equipment, I follow the others to a small forest-green building that looks like it was converted from a residential house. We enter through a garage-like entrance to see rows and rows of tables covered with narrow wooden boxes containing nickel samples. Some have their wooden lids pried off, showing the mineral samples inside. The workers doing the talking, in jeans, t-shirts, and college sweatshirts, read as young, idealistic scientists. They patiently answer questions like “Where is the nickel visible in these ore samples?”, “How deeply do you drill?”, and “Where will the samples go next?”.

Once we have run out of questions, we walk back to the bus mulling over the best response to what we have learned so far about these major industrial extractive projects. Joe Underhill says that the one idea he holds in his mind in response to energy extraction projects is this: Nothing goes away.

Nothing Goes Away

Back on the bus, the conversation turns to differences in environmental regulations between the states. Some states, like Minnesota, have relatively robust, forward-thinking, laws, whereas others, like EnbTexas and Oklahoma (which I am more familiar with) have weaker regulations, that might as well have been written by the corporations themselves. We discuss how energy corporations use their considerable resources to pressure individual state legislators according to the concerns of their constituents, whether those be economic (‘job creation’) or environmental (‘green energy’). I also learn that the dirtiest parts of the extraction process are moved to states with weaker regulations.

Later, when I get home, I will look at Enbridge, Inc.’s website and be shocked at by how much the design and content remind me of online textbooks.

I will also reflect about how the design of the facility we visited channeled our observations towards the technical (which I, at least, didn’t have the qualifications to analyze or argue with) while denying access to decision-makers. The big questions, such as, “Why are oil pipelines so often built in places populated by people who have few resources to fight them?”, “Why are the dirtiest parts of the mining process done in North Dakota, rather than Minnesota?”, or “How will your organization clean up the environment and support people and animals impacted if the process you are describing is not as ‘clean’ as you say it is?” felt almost rude, akin to visiting my local McDonald’s and holding my teenager (who works there) responsible for the McDonald’s corporation’s role in big agriculture.

I believe that this is by design. While large corporations of all kinds control the narrative by limiting public knowledge, it is especially pernicious when the energy industry does it, because the stakes are so high. We mammals are fragile beings. We do not have to see an oil spill, or even know about it, to suffer from its impact.

Nothing goes away.

Conclusion

Visiting the Welcome Water Protectors Center on the first day of Confluence 2 pushed me into the deep end right away, which felt immersive, overwhelming, and inspiring.

Witnessing the Water Protectors support each other, and their community, reinforced for me that struggle and action, like matter, don’t disappear.

Nothing goes away.

Participating in Confluence 2 reinforced for me why I make work that engages with environmental issues and why I ground my teaching in critical theory. Observing how the Welcome Water Protector Center activists support each other, even the way they speak to each other, reminded me of too many times that I put myself into situations and organizations, planning to be the change, only to end up burned out and isolated. I remembered the loneliness I felt being able to see paths forward that were invisible to the people around me.

Nurturing hope is such necessary work, created through kinship, from being around others who can witness the path forward with us, sometimes even lighting the way. In other words, we need each other to create hope because action and change are unsustainable otherwise.

Nothing goes away.

Journey through Confluence — Ashish Kumar

My time at Confluence 2 in Minneapolis resonated deeply with my experiences working with tribal communities in India, in fighting for their land rights and protections from mining activities. This helped me draw connections to struggles faced by Indigenous communities across continents. It provided me, an Indian student, with a unique opportunity to engage with Indigenous communities, activists, and artist-scholars, who possess immense knowledge of the river and struggle to protect it from mining activities and the construction of pipelines. These challenges are deeply rooted in the clash between the traditional values and practices of tribal and Indigenous communities and the profit-driven motives of capitalist and mining companies, often supported by the state. One of the primary obstacles faced by these communities is the lack of legal recognition and protection for their sacred lands and rivers. Due to historical injustices or inadequate legal frameworks, their rights to these lands are often disregarded or easily overridden by powerful corporations seeking to exploit natural resources.

Growing up in a tribal community in India, I was immersed in a way of life deeply intertwined with nature. Our ancestors had imparted the wisdom that the forest was not just a source of sustenance but a sacred entity. It provided us with food, shelter, and medicines, and it played a pivotal role in our cultural and spiritual practices. We understood that the health of the forest directly correlated with the well-being of our community. When mining companies come knocking, tribal communities often find themselves displaced from their ancestral lands. It's a heartbreaking consequence of the profit-driven machine that capitalism fuels. Communities lose their homes, their livelihoods, and their connection to the land that has sustained them for generations.

In our tribal view, the forests and rivers were inseparable. We believed that the forest land and the river water shared a sacred bond, one that sustained life as we knew it. The forests acted as natural filters, ensuring the purity of the rivers. In return, the rivers irrigated our lands, nourishing our crops and providing clean water for our daily needs. We revered this delicate balance and understood that any harm to the forest would disrupt the flow of the river, affecting our very existence. Mining activities don't just destroy physical landscapes; they also obliterate sacred sites and cultural heritage. For tribal communities, the land is intertwined with our identity and spirituality. When those sites are destroyed, a piece of their soul is lost forever. It's a high price to pay for the shiny minerals tucked away beneath the surface.

As modernization advanced in our region, we bore witness to the ruthless exploitation of our cherished forests and rivers. The once vibrant ecosystems that sustained us have been reduced to barren wastelands, devoid of life and teeming with the scars of greed. Our forests are teeming with diverse flora and fauna, were mercilessly clear-cut, leaving behind nothing but stumps and desolation. The rhythmic flow of our rivers, once a lifeline for countless communities, was disrupted by dams and toxic waste from mining operations. Mining corporations and profit-driven interests shamelessly pillaged our land, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. It appeared that the very essence of our existence was under threat, as these resources were being misused for human selfishness. The delicate balance we had revered for generations was being shattered.

The consequences of this rampant exploitation were far-reaching. The loss of biodiversity meant numerous species faced extinction, disrupting the intricate web of life that had evolved over millennia. Indigenous communities who had lived in harmony with nature for centuries found their ancestral lands destroyed and their traditional way of life threatened.

These power structures keep alive a cycle of exploitation and marginalization. These corporations and wealthy individuals exploit the labor and resources of poor communities for their financial gain. It often leads to environmental degradation, displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, and the exacerbation of poverty in urban areas.

Capitalism is driven by the pursuit of profit and tends to prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability, which can result in the depletion of natural resources without considering the consequences for future generations or the ecological balance. Indigenous communities, who have historically lived in harmony with nature and possess valuable traditional knowledge about sustainable practices, are often disregarded or even forcibly removed from their lands to make way for resource extraction projects. Furthermore, capitalism's emphasis on competition and profit maximization fosters an unequal distribution of wealth and power. The economic disparities between different social groups are magnified, leaving marginalized communities with limited access to necessities.

The economic system operates within power structures to prioritize profit over the rights and well-being of Indigenous communities. Big companies, like mining corporations, leverage their financial resources, political influence, and technological advancements to exert control over land and resources. This power imbalance allows them to shape policies, influence decision-making processes, and marginalize the voices of Indigenous communities. Regarding technological advancements, companies leverage these innovations to exert control over land and resources in several ways. These companies utilize cutting-edge mapping and geospatial technologies to identify untapped resources and strategically plan their extraction activities.

This reflection delves into the intricate relationship between capitalism, mining companies, and tribal communities, examining the power dynamics at play their profound impacts on Indigenous populations in India and the United States. I aim to delve into my own journey, highlighting the similarities between the issues faced by tribal communities around mining in India and the USA within the context of the Mississippi River corridor. By unraveling historical contexts, analyzing the profit-driven nature of mining corporations, and exploring the socio-cultural and environmental consequences faced by tribal communities, I aim to shed light on the often-overlooked narratives of those most affected. By examining the power structures inherent in capitalism, the forest rights movement in India, and the fight for community-led conservation, we can better understand the shared challenges faced by these communities and the importance of collective action. Drawing upon my experiences at the Welcome Water Protector Center and my background in India, I will explore the shared struggles faced by these communities in their fight to preserve their sacred lands and their connection to them.

In both India and the USA, one of the primary challenges faced by the Indigenous communities is encroachment upon their traditional territories. Mining operations often require large areas of land, leading to deforestation, habitat destruction, and displacement of Indigenous populations. This not only disrupts their connection to the land but also threatens their livelihoods, which are often dependent on natural resources found in these areas. The weight of governmental policies, often prioritizing economic interests over environmental and social justice, suppresses their voices, leading to marginalization and disempowerment. The extraction of valuable resources threatens not only their livelihoods but also the ecological balance crucial to their way of life.

One striking parallel between India and the USA lies in the significant environmental impacts of mining activities on the Mississippi River corridor and various regions in India. Both areas have witnessed the devastating consequences of unchecked mining operations, including water pollution, deforestation, and soil degradation. These activities disrupt the delicate balance of ecosystems, negatively affecting biodiversity and the cultural significance of rivers for Indigenous communities. The contamination and alteration of the natural flow of rivers threaten not only the environment but also the cultural identities of these communities.

In both India and the USA, due to mining, communities have experienced a lack of adequate protection. Legal frameworks and regulations often fall short of safeguarding the rights and well-being of Indigenous peoples. Even when rights are won after long struggles, they are simply bypassed later. Tribal communities are vulnerable to exploitation and displacement. One of the primary challenges faced by Indigenous peoples in both countries is the limited consultation process surrounding mining projects. Most of the decisions regarding mining activities are made without proper consultation or consent from the affected communities. This disregard for their input not only undermines their rights but also perpetuates a cycle of exploitation and displacement. Regulations that prioritize community consent, environmental sustainability, and equitable benefits could help, but current legal frameworks exacerbate the challenges faced by these communities.

To truly unveil the power dynamics at play, it helps to examine specific examples of how capitalism and mining have affected tribal communities. Case studies from India and the U.S. shed light on the tangible consequences faced by Indigenous populations. In one remarkable village in India, our community stood united against the forest department's unjust eviction orders. They claimed that our presence was a threat to the forest and its tiger population. However, we knew that we had coexisted harmoniously with these creatures for ages, respecting and living alongside them. Organizations like ours fought tirelessly to secure our rights and the rights of six other villages facing eviction. We were determined to preserve our way of life and protect our forests. While we successfully secured our rights and prevented eviction in these villages, our fight is far from over. We continue to advocate for the rights of Indigenous communities, emphasizing the vital importance of community-led conservation and the role of forest rights in preserving our lands. Our story is a testament to the resilience and determination of Indigenous communities worldwide in their battle for justice and the protection of their sacred lands and rivers.

My journey from India to the USA, from tribal communities to Confluence 2, has reaffirmed the global significance of Indigenous struggles to protect their lands and rivers. It highlights the shared challenges faced by these communities, challenges that transcend borders and cultures. The Forest Rights Act has proven to be an indispensable tool in our fight for preservation, offering hope and empowerment in the face of adversity. As we continue to stand together, inspired by the story of the village that defied eviction, we recognize the importance of collective action, cross-cultural learning, and the global solidarity needed to secure a sustainable and just future for all Indigenous communities and our precious natural resources.

India and the USA share a common struggle for land preservation and the protection of Mother Earth. Indigenous communities in both countries have fought tirelessly for their rights, working to save their lands and preserve their cultural heritage. Confluence 2 provided an invaluable platform to connect with individuals who share this common struggle, fostering a sense of global solidarity and the understanding that the fight for environmental justice transcends national boundaries.

Both India and the USA are democratic nations that uphold principles of equality, justice, and the protection of human rights. However, the implementation and enforcement of policies remains uneven, affecting the extent of protection afforded to tribal mining communities. Stronger democratic institutions and policies that prioritize community participation, consent, and sustainable resource management can help rebalance power dynamics and protect the rights and lands of Indigenous communities.

The unregulated pursuit of profit is antithetical to a concept of collective welfare. The only real way to guarantee community protections is to put an end to the profit system which destroys the environment and people for profits. We need a system that does not prioritize profit, but instead prioritizes the needs of humanity. A system that learns from the way Indigenous peoples lived all over the world before class society. A system where humans live in harmony with nature and each other, and produce only for human need, not profit. In a democratic rights system where humans plan and produce collectively for the good of all.