What is environmental justice? Is it a movement? Is it an outcome? The term was unfamiliar to me until midway through my time in college, but its use now seems commonplace. I grew up in Minneapolis’s hippy-dippy Seward neighborhood during an era where Minnesota was celebrating increasingly diverse, multicultural communities and ignoring the ways in which redlining and other factors contributed to what, Richard Rothstein argues, appears to be a de facto segregated society but is, in fact, one segregated de jure — by laws, policies, and other actions of the state.[1] There were clear signs of pollution across South Minneapolis: I remember biking along the Midtown Greenway, holding my breath against the thick smell of asphalt belching from the Bituminous Roadways factory. What distinguished my experience from that of my neighbors in East Phillips, however, was distance. My infrequent collisions with visible pollution were (and still are) the everyday, lived reality of thousands of residents living near Bituminous Roadways, the Smith Foundry, the Hennepin Environmental Recycling Center, and countless other industrial polluters across the Twin Cities metro area.

It was with this personal context in mind that I returned to the Twin Cities in 2018, with a joint major in Environmental Studies & Sociology and foggy job prospects. A series of roles in nonprofits and direct service brought me to Saint Paul’s East Side, working with unhoused families and Indigenous youth. In March of 2020, two weeks before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I started a two-year stint with a Native-led environmental organization based on the East Side, focusing on the preservation of Dakota sacred sites, the remediation and expansion of public green spaces, and increased access to environmental education and cultural connections across the east metro. In 2021, seeing the impacts of pollution and inadequate food & transit access across the East Side, I secured unrestricted funding from the Trust for Public Land and restricted funding from the EPA to establish a role for an Environmental Justice Organizer. Yet, while I was proud to have found resources to devote attention to neighborhood-specific environmental issues, I found myself somewhat concerned about the implications of professionalizing environmental justice. That concern has carried through to my current role at Macalester’s Community Engagement Center, where I work to connect students and community organizations across the Twin Cities on a variety of topics, but see environmental justice as a throughline of many local conversations and issues. What follows, then, is my thought process, borne out over the course of the Fall 2023 semester, on how environmental justice fits (or doesn’t) into bottom-up and top-down spaces; and how young people should seek to understand environmental justice itself.

Since a largely Black, Christian, poor, rural community protested the intrusion of a toxic landfill in Warren County, North Carolina, the phrase “environmental justice” has proliferated in its use and interpretation. Oppressed and marginalized communities have long protested the degradation of their neighborhoods and surrounding ecosystems at the hands of industrial pollution, but the 1982 Warren County protests marked a watershed moment in the American public conscience. Despite the tragic fact that the landfill was ultimately installed (though this was more an indictment of the racism embedded in North Carolina’s public administration than a failure on behalf of the protesting community), publication of the protests on the heels of the burgeoning environmental movement and the fraught racial politics of the civil rights era was one of the first instances in which an environmental conflict was framed as both a hazard to public health and a matter of racial & socio-economic justice.

In an “official” sense, environmental justice has been a priority of the federal government since 1994, when the Clinton administration issued an executive order mandating that the Environmental Protection Agency:

identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income populations, to the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law; develop a strategy for implementing environmental justice; [and] promote nondiscrimination in federal programs that affect human health and the environment, as well as provide minority and low-income communities access to public information and public participation. [2]

In practice, however, the federal government has demonstrated a less-than-stellar track record when it comes to carrying out this mandate. Nestled within the broader scope of the EPA’s responsibilities to America’s ecosystem, environmental justice is one of many pie-in-the-sky priorities that has been sidelined across multiple presidential administrations and suffered from the same whiplash of inconsistent funding, poor legislative enforcement, and more recently, severe cutbacks that have plagued the agency since its inception in 1970. This is not to say that no advancements toward environmental justice have been made; rather, the way in which both the environment and its socio-political implications have been discussed by the state has rarely resulted in improvements in the lived experience of those most affected by industrial pollution and environmental degradation in American communities.

With this context in mind, myself and Kiristina Sailiata, Assistant Professor of American Studies at Macalester College, set out to develop a course exploring the evolving concept of environmental justice and seeking to connect college students with environmental justice issues and campaigns currently being waged on the grassroots level and within a tangible geographical community. This summer, Kiri and I sat down and mapped out a number of ongoing public campaigns — in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis & St. Paul) as well as in greater Minnesota — self-identified by organizers as environmental justice issues. We spent a fair amount of time calculating the logistics of transporting students to sites in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and northern Minnesota; we also identified campaigns, organizations, and individuals with which we had existing relationships, figuring that it would be unwise to dive into a campaign with which we had no familiarity. In addition, we weighed the importance of academic study and literature reviews against the incomparable value of qualitative experiences shared in community spaces, ultimately landing on the format of a 1-credit college course.

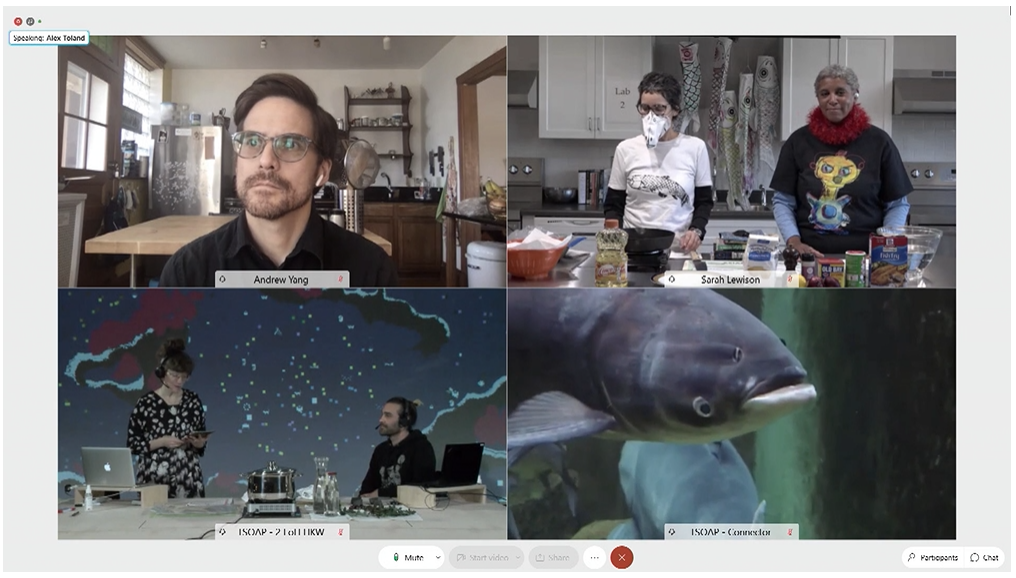

Starting in September, we met with a group of ten students eight times throughout the Fall 2023 semester, with three off-campus “field trips,” two on-campus visits with community partners, a walkthrough and discussion of the Insurgent Ecologies exhibit (an art exhibit exploring these themes which recently traveled up the Mississippi to Macalester from Antenna Gallery in New Orleans), and two in-class sessions. This structure allowed us to prioritize local concepts of environmental justice over more academic definitions and gave our students the chance to witness and sit with the nuances of grassroots movement work. Just as important to our goals for the course however, was that this structure gave our students a glimpse into the process of community organizing. While it would be unwise to try to cram an organizing bootcamp into a 1-credit, 8-session undergraduate class, we designed our visits with community partners, our in-class discussions, and a minimal amount of out-of-class assignments to highlight some of the basic principles that underpin sustainable and powerful social movements. Below, I summarize a selection of where we went and whom we spoke with:

On a visit to a small property outside of the northern Minnesota town of Palisade, we spoke with staff and community members from Honor the Earth who had been involved in the multi-year efforts to block Enbridge’s Line 3 oil pipeline from running through 1854 Treaty and other tribal lands, under the Mississippi River, and throughout fragile rural ecosystems. We gathered at a space that had served as the Water Protectors Welcome Center during that campaign, where hundreds of community members gathered for rallies, direct actions, meals, shelter, political education, and more. Over a shared meal, we learned how the space had served as a back-end support for years of movement work, and how it was now evolving into a hub for environmental community organizing training across Turtle Island. We also met with Leanna Goose, a staff member at Honor the Earth and a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, who, with her partner and young children, brought us to a nearby lake to demonstrate the traditional Anishinaabe practice of harvesting wild rice, a practice that is severely threatened by climate change and the encroachment of industry throughout the region.

On a subsequent Saturday, we packed into a yellow school bus and drove to a number of sites across Minneapolis’s Northside with Roxxanne O’Brien of Community Members for Environmental Justice. As we wound south along the west bank of the Mississippi from the Lowry Avenue Bridge toward downtown, students noted the stark differences in the riverside infrastructure. Whereas the riverfront on the predominantly Black Northside was a clutter of active and inactive industrial sheds, equipment, raw materials, and concrete lots, downtown boasted wide walk/bike paths, tree cover, new-build apartments and a vibrant commercial area. For many students (including some from the Twin Cities), this visual reminder of environmental racism conveyed more than we as instructors could hope to get across in class. But what students also gained from this experience was a greater understanding of the pace of grassroots work: as O’Brien shared with us during the tour and a subsequent on-campus discussion, her efforts to close the Northern Metals metal shredding facility, a long-time polluter in the neighborhood, took almost a decade of fervent advocacy; now that the business has been held (somewhat) accountable for its countless code violations, it is the future use of the site that is contested.

Back on campus, we spoke with Fernanda Acosta of Unidos MN. We chose to highlight the work of an organization that was not explicitly formed with environmental justice as its charge. Despite its origins in advocating for the rights and protections of undocumented immigrants in Minnesota, Unidos is a wonderful example of the utility of grassroots community organizing. In its relatively short history, the organization has grown to incorporate a wide base of migrants from within and beyond the Latinx community, and it has embraced a coalitional approach to legislative advocacy. In 2022, Unidos was instrumental in major campaigns at the Minnesota legislature and at the municipal level, securing universal driver’s licenses for all Minnesotans, the incorporation of mandatory ethnic studies curricula in Minnesota’s public high schools, and securing the designation of millions of dollars for community-based climate equity initiatives in the city of Minneapolis. Now, Unidos and its allies across the state are poised to have considerable input over how federal climate funding is distributed, with the potential to improve the lived experiences of working class people across the Twin Cities.

Each of the above blurbs is no more than a rough overview of our attempt at experiential learning opportunities. There were more discussions and topic threads than can be captured here. What is important to note is that our purpose with each interaction was not to fully detail the trials and triumphs of a given campaign, but rather to expose undergraduate students to the on-the-ground realities of community-based environmental justice work. By comparing and contrasting what these efforts look like in rural vs. urban areas; by exploring how environmental justice translates (or doesn’t) to the dizzying arenas of municipal, state and federal legislation; and by emphasizing the overwhelming importance to any grassroots movement of building and maintaining relationships, we hoped to give students a basic idea of the landscape of environmental justice in Minnesota.

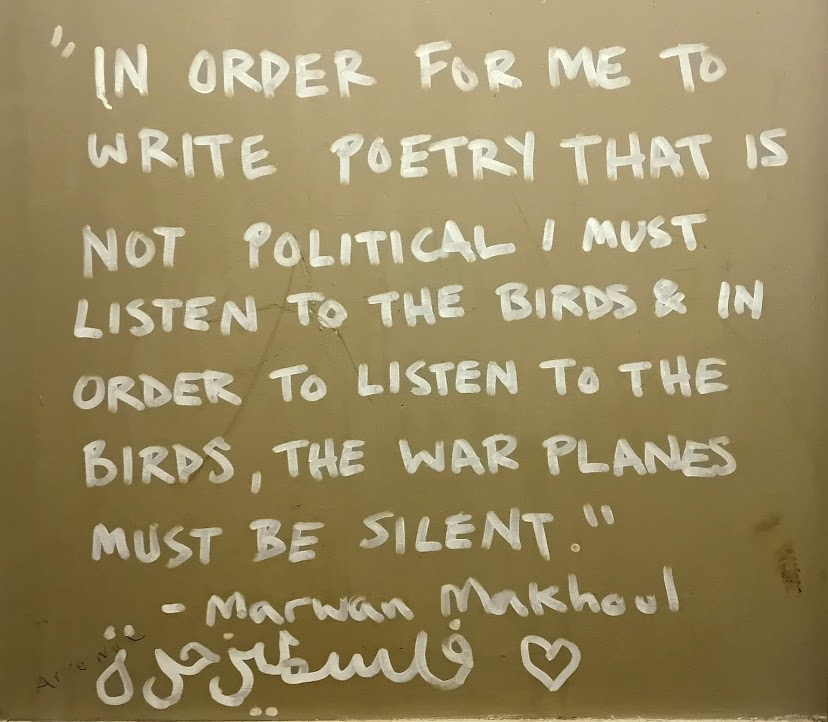

It bears mentioning that one month into the course, the world was rocked by the brutal assault on Israel’s southern border by Hamas and other armed Palestinian groups, and, in the days and months that followed, by Israel’s still-ongoing brutal retaliation in the Occupied Territories. While this course was not ostensibly global in scope, and while we did not have the time and space to fully and appropriately approach questions of global environmental justice, we nevertheless found it necessary to address the unfathomable loss and destruction suffered by thousands of Israeli citizens on October 7th and by millions of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank in the months since. At this moment, we found David Nguib Pellow’s characterization of the longstanding conflict, that “this struggle involves power imbalances between different religious and ethnic communities over history, memory, land, water, agriculture, and the very right to exist,” to be particularly instructive. [3]

So, what is environmental justice? Our hope is that students walked away from this course with no single definition or picture in their mind. Our hope is that students found value in campaigns that draw almost exclusively on volunteer labor and neighborhood-level community engagement, and comparable (if not equal) value in campaigns that work with non-profit professionals and elected officials in the legislative arena. Our hope is that students find value and meaning in the expression of environmental injustice through art and other media. Our hope is that students find value in relational organizing as a habit. The midterm assignment for this course tasked each student with participating in two one-to-one conversations: one in which they were asked about their self-interest, their motivations, the experiences that shaped them and the spaces they want to be in; and another in which they asked those questions of a fellow student. The final assignment for this course asked students to look ahead six months, 12 months into the future. Regardless of their major, plans to study abroad, goals for internships, etc., we asked students to express a personal commitment to environmental justice and articulate specific goals. We certainly did not expect students to spearhead their own campaigns or devote their full time to any single cause. But what we did see was an admirable level of reflection and curiosity: some students expressed a desire to investigate environmental justice issues in their home communities; others demonstrated an eagerness to connect further with their peers, and even with some of our community partners.

Within the scope of a 1-credit course, and having met with this group of students only a handful of times, it was heartwarming to see young people truly embracing environmental justice not as a single set outcome, and not as a single-issue point of focus, but as something to be practiced and pushed for and built, brick by brick. As for what this course has taught me, I’m still deciding. I reflect on my limited perceptions of environmental justice when I was in college, and wish I had found specific campaigns to get involved with. I look at my previous role on Saint Paul’s East Side and feel that there is much work to be done (there will always be much work to be done). I look at my role here at Macalester and see an opportunity to leverage institutional resources and knowledge — both within and beyond the classroom — for the benefit of communities most impacted by environmental issues. I am unsure whether I will teach this course in the future, but that’s beside the point. I do know that there are many young people out there (and many not-so-young people like myself) who benefit greatly from viewing environmental justice as a relational practice; and I am optimistic that the more we embrace this perspective, the more we are able, to paraphrase Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to ride out the long arc of the moral universe on its winding path toward justice.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. 2017. New York: Liveright.

United States, Executive Order of the President [William Clinton]. Executive Order 12898: Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. 16 February 1994. Federal Register, vol. 59. no. 32. (Alternatively listed as 59 FR 7629.)

Pellow, David N. “The Israel/Palestine Conflict as an Environmental Justice Struggle.” In What is Critical Environmental Justice? 2018. Cambridge: Polity Press.