(Originally published for the Anthropocene Curriculum.)

“You’ve got to eat it to save it” is a popular saying among slow food producers and eaters who work to preserve the biodiversity of native foods and food traditions facing extinction. It is a tried and true method of engagement. There are many rewards and pleasures that come from eating rare and carefully preserved foods. These foods, like the American wild persimmon found in the Midwest, often circulate story and mythology in and of themselves. It behooves us to pay attention not only to these foods for their ecologic significance, but also to the accompanying narratives and from what perspective they are told. There are many hidden hierarchies in these stories that lead to an accumulated homogenization of cultural capital. Like seeds, we pass these stories from one generation to the next by what comes natural to us: our collective practice of cooking and eating. When we consciously eat these foods, we participate in an ideological arc of past, grounded in the present and future.

Baked into the idea of “eating it to save it” is the anthropocentric relationship that humans have with biodiversity through breeding and natural selection. As much as the rise and fall of biodiversity on Earth has happened outside the realm of human interaction, the biodiversity of what we call food has very much to do with human interaction. This relationship has been well documented throughout time, and especially here, in the American Bottom—the extensive floodplains of the East St. Louis region. The ongoing work of paleoethnobotanists, whose archeological data goes back some 5,000 years, demonstrates how humans have manipulated plant productivity through seed selection from prehistory to present times.11See “Field Station 3: Post-natural Landscapes,” https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/events/field-station-3-post-natural-landscapes. To understand that history helps us to understand farmland as a kind of cultural landscape where the production of space and human patterns are accumulated and impressed upon the contours of the natural environment,22Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997. chapter 2, pp. 15. until we can no longer identify what came before the human.

We can seek out biological and cultural remnants of prehuman edible matter in any landscape. But the more we look, the more we find ourselves intertwined at every level. This project, Edible Encounters along the Mississippi, used a methodology of enactment and encounter to investigate examples of native biodiversity and foods of significance in the Confluence region. Working with edible matter can be particularly thrilling because it is alive. Like us, plants and seeds and animals are biologically programmed to reproduce. We can attempt to seek this life through an exploration of the landscape in the liminal sidelines of the river, looking for undomesticated, latent, lost, or forgotten examples of what has become wild.

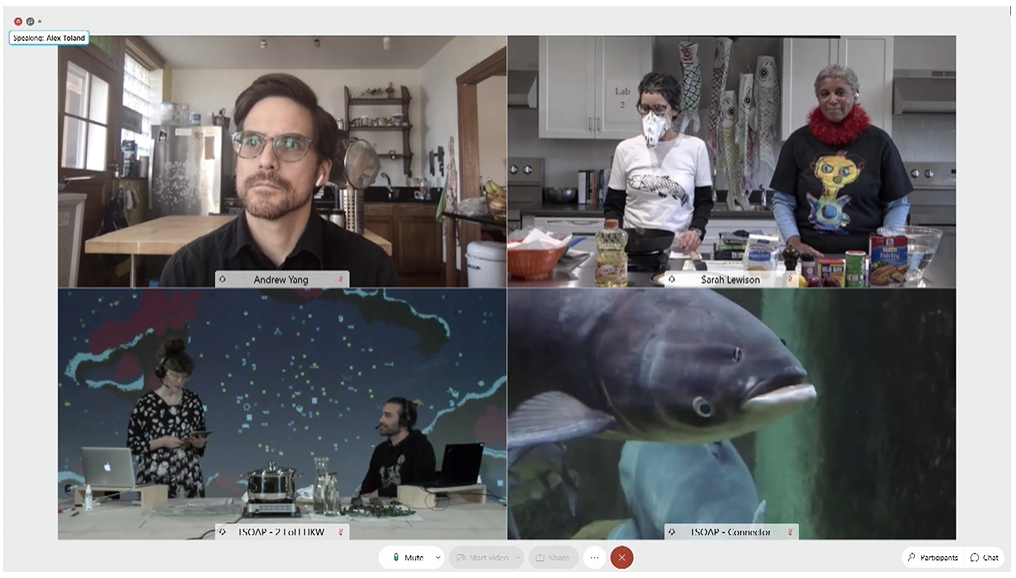

As an instructive investigation—on the river, with students—Edible Encounters presented foods linked to place. It used specific assemblages of vegetables, nuts, beans, and other foods as curated objects that were then prepared in a group encounter and transformed into meals that have linkages to histories of place. The foods are intended to be eaten in order to be “saved,” or at least preserved, through a continuity of experience placed in a collective memory.

Edible Encounters also pursued relations between food and place in unforeseen encounters with the wild (what still gets called “wilderness”)33Cronon William, Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. New York: W. W. Norton, 1995, pp. 69-90., offering a temporal investigation in what the place has to offer through foraging. Foraging asks us to look in detail at the landscape and ask, “What is edible here?” It enables us to seek real time and sometimes fleeting assemblages of edible material. Importantly, it calls upon the capital of knowledge and the currency of culture to know how to recognize the findings and what to do with them. Foraging along the banks of the Mississippi River offers an opportunity to recognize remnants of ecologic autonomy in pockets of wilderness contrasted against the larger surroundings of industry and agricultural monocultures. It allows us to imagine narratives and micro eco-communities that diverge from the vast monocultures and veer from the anthropocenic.

If you look at farmland adjacent to the Mississippi River today, you will not be shocked to see that the majority of field crops are contemporary monocultures, like corn and soy. These productive landscapes are the very opposite of biodiversity. In fact, fifteen or so miles of river adjacent to St. Louis and Illinois represents the transfer of so much commodity grain production infrastructure from land to water that it is known as the Agriculture Coast. From here, the grain barges move down the river to distribute their cargo for processing and export. Looking carefully at the places affected by the industrialized river economy, we see a well-worn landscape of urbanism, industry, and monoculture that belies this local industry’s significance at the global scale.

The influence of corn in particular is worth lingering on for a moment. As one of the world’s central commodities, corn plays a critical role in global food security today. It is also one of the most quintessential crops within the American identity. This elevated status may relate to the cultural emphasis on corn for the role it played in human settlement and agriculture, as it spread from its origin in Central America throughout North America. In the pre-Columbian city of Cahokia, adjacent to the Mississippi River and along the American Bottom, archaeologists date the adoption of maize at roughly 1000 ce. But it was only in the last century that it grew to become the dominant form of agricultural identity in the Midwest.

Edible Encounters gave us an opportunity to observe the contrast between the wild bursts of biodiversity in the marginal areas along the river and the widespread control of nature exemplified by the endless cornfields in this region. These series of edible encounters and territorial mash-ups offered interpretations of foods that have bioregional origins or are part of long-standing Indigenous traditions or both. It was an opportunity to look to Indigenous knowledge, tradition, and creativity to build collective narratives and memory through the shared experience of taste. Like the Mississippi River itself, these encounters paired planning with spontaneity and required participants to go with the flow.